The location had to be in a dark sky, where light pollution wouldn’t hinder the detail of the Pleiades, especially with the Moon already at 19% illumination and washing out some of the detail. After scouring Google Earth, I found a tree in a Class 2 dark sky location and planned to check it out before the date in March.

I never made it. Life got busy, and I couldn’t justify the three-hour drive to scout the area. As March 28th approached and the weather forecast predicted clear skies, I felt unprepared. I thought about finding a better location but couldn’t think of anything. So, on the night of the 28th, I headed to the location sight unseen. Thankfully, with tools like PlanIt, I was able to position myself correctly for the shoot.

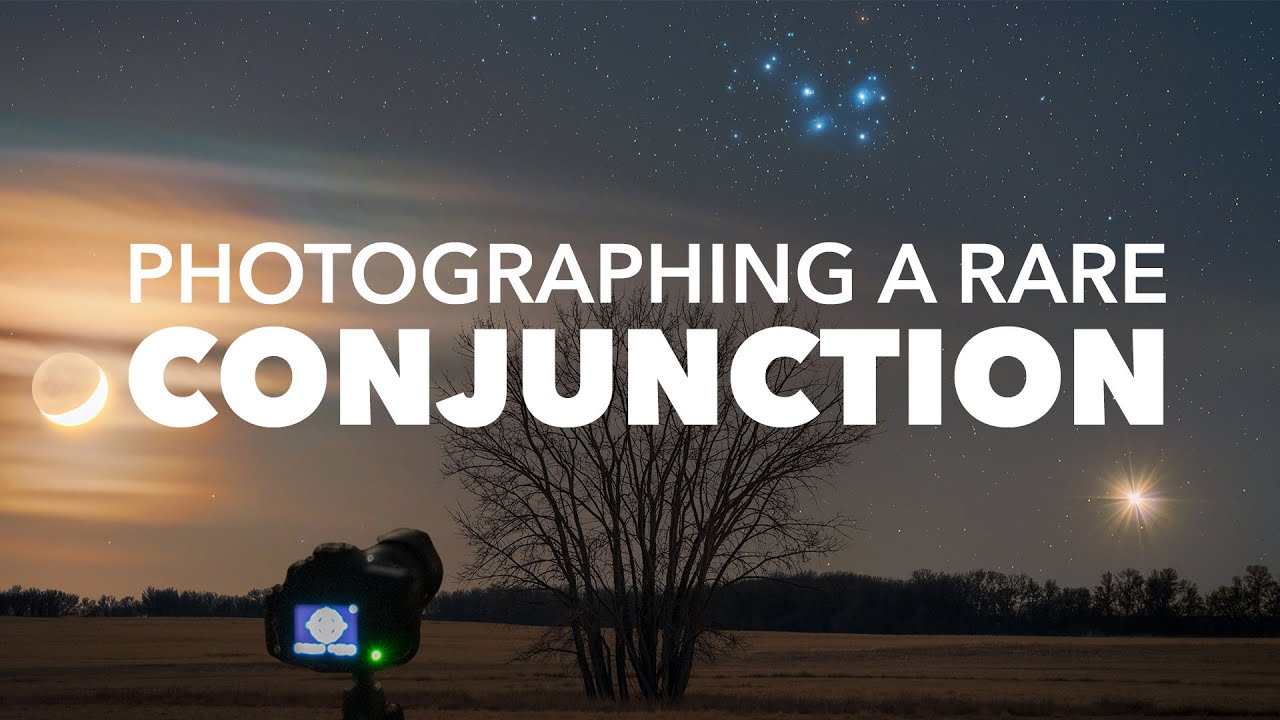

I set up my tripod around 10:40 PM and photographed the foreground first, using the moonlight to naturally illuminate the landscape when the Moon was higher in the sky. Then, I turned on my tracker and took 36 one-minute exposures for Venus and the Pleiades. This exposure time overexposed the Moon, so I switched the exposure to 30 seconds at f/6.7, set my tracker to lunar mode, and took another 20 exposures with those settings.

This shoot was certainly a challenge due to the brightness of the Moon and Venus, but I’m pleased with what I managed to capture. These three astronomical objects wouldn’t be this close together for decades, so I thought filming behind-the-scenes footage of the event would be a great way to commemorate it (above). It will be fun to look back on this moment when—if—I reach the age of 72 and these three objects align again. For those who are interested, mark your calendars for April 3rd, 2060. On that date, the Pleiades, Venus, and the Moon will align again, and, if that isn’t enough, Saturn and Jupiter will join the party, filling a single telephoto frame, for the ultimate deepscape.